ONE OR TWO WORDS?

Everybody who has been learning Polish, whether during a group course (you can learn more abort courses for foreigners here), or in individual lessons, must have noticed that there are words in Polish that sound or are spelled the same but have a different meaning. Obviously, we are talking about homonyms that can sometimes amuse students but at other times simply confuse them.

MAMY MAMY – REPETITION OR A DIFFERENT MEANING?

Let us take a closer look at the word mamy, which in the Polish language is the 1st person of plural form of the verb mieć in the present tense and looks quite innocent. What does then mamy mamy mean then? Is it just an erroneous repetition or a piece of information stating that we have mothers? Mamy is also a plural form of the noun mama (mother).

Thanks to homonyms one can state while playing cards with friends: nie dam dam, that is I’m not going to give away the queens (in Polish, the playing card called queen is referred to as a lady i.e. dama). The word dam denotes here both the 1st person singular form of the verb dać (to give) in the future tense and the genitive plural form of the noun dama (literally a lady; in cards, meaning a queen). Here we are dealing with the similarity between two distinct forms resulting from inflection of two different words.

MOŻE ON MOŻE POJECHAĆ NAD MORZE

In the beginning some of you might be surprised by the information that the word może is the 3rd person singular form of the verb móc as well as a way to express uncertainty. Additionally, there comes yet another morze (this time spelled with rz), which means sea. We have here then as many as three words that sound the same and on top of that two of them are spelled identically, however, their meanings have nothing to do with each other. There are many such words in the Polish language. Sometimes two different verbs can have identically pronounced forms in different tenses:

Po podróży goście długo myli się przed kolacją

(the verb myć się – to wash oneself - in the past tense 3rd person plural form).

but

Saper myli się tylko jeden raz

(the verb mylić się – to make a mistake - in the present tense 3rd person singular form).

CONTEXT IS YOUR BEST FRIEND

To avoid making mistakes related to homonyms, when we have any doubts it is worth paying extra attention to the context. From the context we will know whether our interlocutor is using the word ranny meaning something that takes place in the morning hours:

Tuż po wschodzie słońca słuchałem śpiewu rannych ptaków

Or meaning “wounded”:

Kilka rannych ptaków czekało na pomoc lekarza.

To był duży bal charytatywny, w którym wzięło udział wielu znanych ludzi (bal – a big dance party, a ball).

To był duży bal drewna i ludzie nie mogli go podnieść bez pomocy maszyn (bal – a log of wood).

You can find more interesting facts about the Polish language on our FB profile.

piątek, 27 listopada 2015

czwartek, 12 listopada 2015

Ó – A SHORT STORY OF A CERTAIN POLISH LETTER

WHERE DID Ó COME FROM?

As early as during their first Polish language lessons, when working on the Polish alphabet, the course participants are stunned by some of the Polish letters. However, none of these letters, neither vowels ą / ę, nor ć, dź, ś, ż, ź, absorb the foreigners as much as the small, beautiful and mysterious ó. What's the point of this letter, how do you pronounce it, and in which words does it occur? Ladies and gentlemen, the hero of today's episode is the letter Ó.

EVOLUTION OF Ó

In a nutshell, there used to exist short and long vowels in the Polish language. The letter were recorded with a characteristic, long dash above the a, e, i, u, and consequently also above o (ā, ē, ī, ō, ū). While the other vowels disappeared over time, ó has remained as a sort of peculiar relic of the past. Still, there are a lot of words in Polish that have kept the historical spelling based on the old pronunciation (chór – choir, góra – mountain, król - king, mózg - brain, późno – late, źródło - water spring, ogórek - cucumber, etc.).

U OR Ó? WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE AND WHERE CAN WE ENCOUNTER Ó?

This is a very common question in a Polish language course. Students are concerned with the fact that we have two letters that sound the same. Is their pronunciation really the same? Are the u in Ursula (a Polish female name) and the ó in Józef (a Polish male name) pronounced in the same way? Well, yes! Nowadays, there is only a spelling difference between these letters. The letter ó occurs very often in word endings: - ów, - ówna, - ówka (Kraków – the city of Cracow, kreskówka - cartoon, lodówka – refrigerator, etc.). You will never see it at the end of a word, and very rarely at the beginning (ósma - eighth, ósemka – the number eight, ów – that one, ówczesny – of that time).

Do you like the letter Ó slightly more now?

You can find more information about the Polish language on our FB profile

As early as during their first Polish language lessons, when working on the Polish alphabet, the course participants are stunned by some of the Polish letters. However, none of these letters, neither vowels ą / ę, nor ć, dź, ś, ż, ź, absorb the foreigners as much as the small, beautiful and mysterious ó. What's the point of this letter, how do you pronounce it, and in which words does it occur? Ladies and gentlemen, the hero of today's episode is the letter Ó.

EVOLUTION OF Ó

In a nutshell, there used to exist short and long vowels in the Polish language. The letter were recorded with a characteristic, long dash above the a, e, i, u, and consequently also above o (ā, ē, ī, ō, ū). While the other vowels disappeared over time, ó has remained as a sort of peculiar relic of the past. Still, there are a lot of words in Polish that have kept the historical spelling based on the old pronunciation (chór – choir, góra – mountain, król - king, mózg - brain, późno – late, źródło - water spring, ogórek - cucumber, etc.).

U OR Ó? WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE AND WHERE CAN WE ENCOUNTER Ó?

This is a very common question in a Polish language course. Students are concerned with the fact that we have two letters that sound the same. Is their pronunciation really the same? Are the u in Ursula (a Polish female name) and the ó in Józef (a Polish male name) pronounced in the same way? Well, yes! Nowadays, there is only a spelling difference between these letters. The letter ó occurs very often in word endings: - ów, - ówna, - ówka (Kraków – the city of Cracow, kreskówka - cartoon, lodówka – refrigerator, etc.). You will never see it at the end of a word, and very rarely at the beginning (ósma - eighth, ósemka – the number eight, ów – that one, ówczesny – of that time).

Do you like the letter Ó slightly more now?

You can find more information about the Polish language on our FB profile

piątek, 30 października 2015

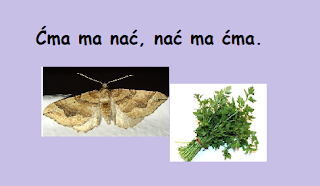

EXERCISE FOR YOUR TONGUE – POLISH TONGUE-TWISTERS

EVERY LANGUAGE HAS ITS DARK SIDE… OF PRONUNCIATION

When we begin our adventure with learning a foreign language, apart from practical phrases and expressions, we are bound to encounter tongue-twisters. Such combinations of words are usually very difficult to repeat and every language has that “something” that causes serious problems with pronunciation.

Among many of the foreigners learning Polish there is a widespread conviction that this language has very complex phonetics. Well, if you happen to overhear Polish people talking to each other on the streets, you might, indeed, conclude that they are making some sort of whistling and crackling sounds. The popular tongue-twisters that your Polish acquaintances tend to use to “frighten” the foreigners, only seem to prove that notion.

POLISH IS NOT AS HORRIBLE AS IT MAY SEEM

Don’t be scared, though! During a Polish language course, especially the one for beginners (if you are looking for a good course, you should definitely look here), you won’t need to repeat the famous verses about a beetle making sounds in the reeds in Szczebrzeszyn (pol. chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinie w Szczebrzeszynie) or about the postmaster from Tczew dancing cha-cha (pol. poczmistrz z Tczewa tańczący cza-czę). In fact, tongue-twisters, in spite of their name, are not meant to twist or break your tongue, and even less so to discourage you from learning, but to practice what’s difficult and troublesome. That is why you shouldn’t be afraid of them. You simply need to get used to the sound of the language first, and then practise phrases and words which are of more practical use, such as Jak się pan nazywa? rather than the abovementioned chrząszcz or piegża (white-throated warbler). Only then, just for fun, can you try to repeat some of the Polish tongue-twisters. And there are quite a few of them.

A CHALLENGE NOT ONLY FOR A FOREIGNER

We shouldn’t forget that these tongue-twisters have appeared not without a reason and some of them are a great challenge even for the native Polish speakers. All consonant clusters that are pronounced with such beautiful whistling and whishing are not hard for native speakers to pronounce as long as they appear in separate words. However, when too many of such words come together, they Poles might “over-whish it” and instead of saying: Sasza szedł suchą szosą (Sasha was walking along a dry road), you’ll get something like: Szasza szedł szuszą szoszą.

It is just as hard to pronounce the words such as artyleria (artillery), artyleryjski (adjective derived from the noun artillery) or rewolwer (revolver). In the Polish language “r” and “l” are close in articulation point (by the way, artykulacja is another difficult word) and therefore it’s easy to make a mistake.

More Polish tongue-twisters and interesting facts about the Polish language you can find on our FB profile

So, if any of your Polish acquaintances asks you to repeat: cesarz czesze cesarzową, a cesarzowa czesze cesarza (the emperor is combing the empress and the empress is combing the emperor), you can suggest that you will give it a try, but in exchange you should ask them to repeat: król Karol kupił królowej Karolinie korale koloru koralowego (king Karol has bought a bead necklace of coral colour for queen Karolina). You can rest assured that it’s not going to be an easy task.

Let’s not forget that most Poles have been learning these tongue-twisters all their lives. When they rattle them off without pausing for breath, you can be sure they have done it many times before.

And if you want to pleasantly surprise both the Poles and foreigners speaking Polish, it is enough, while spending time in your cosy domesticity, to memorize one of such tongue-twisters (in case of difficulties just ask your teacher for help), and then to show what you can do. And then, it will turn out that Polish is easy after all (and especially so, when you learn it at Po Polsku)!

When we begin our adventure with learning a foreign language, apart from practical phrases and expressions, we are bound to encounter tongue-twisters. Such combinations of words are usually very difficult to repeat and every language has that “something” that causes serious problems with pronunciation.

Among many of the foreigners learning Polish there is a widespread conviction that this language has very complex phonetics. Well, if you happen to overhear Polish people talking to each other on the streets, you might, indeed, conclude that they are making some sort of whistling and crackling sounds. The popular tongue-twisters that your Polish acquaintances tend to use to “frighten” the foreigners, only seem to prove that notion.

POLISH IS NOT AS HORRIBLE AS IT MAY SEEM

Don’t be scared, though! During a Polish language course, especially the one for beginners (if you are looking for a good course, you should definitely look here), you won’t need to repeat the famous verses about a beetle making sounds in the reeds in Szczebrzeszyn (pol. chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinie w Szczebrzeszynie) or about the postmaster from Tczew dancing cha-cha (pol. poczmistrz z Tczewa tańczący cza-czę). In fact, tongue-twisters, in spite of their name, are not meant to twist or break your tongue, and even less so to discourage you from learning, but to practice what’s difficult and troublesome. That is why you shouldn’t be afraid of them. You simply need to get used to the sound of the language first, and then practise phrases and words which are of more practical use, such as Jak się pan nazywa? rather than the abovementioned chrząszcz or piegża (white-throated warbler). Only then, just for fun, can you try to repeat some of the Polish tongue-twisters. And there are quite a few of them.

A CHALLENGE NOT ONLY FOR A FOREIGNER

We shouldn’t forget that these tongue-twisters have appeared not without a reason and some of them are a great challenge even for the native Polish speakers. All consonant clusters that are pronounced with such beautiful whistling and whishing are not hard for native speakers to pronounce as long as they appear in separate words. However, when too many of such words come together, they Poles might “over-whish it” and instead of saying: Sasza szedł suchą szosą (Sasha was walking along a dry road), you’ll get something like: Szasza szedł szuszą szoszą.

It is just as hard to pronounce the words such as artyleria (artillery), artyleryjski (adjective derived from the noun artillery) or rewolwer (revolver). In the Polish language “r” and “l” are close in articulation point (by the way, artykulacja is another difficult word) and therefore it’s easy to make a mistake.

More Polish tongue-twisters and interesting facts about the Polish language you can find on our FB profile

So, if any of your Polish acquaintances asks you to repeat: cesarz czesze cesarzową, a cesarzowa czesze cesarza (the emperor is combing the empress and the empress is combing the emperor), you can suggest that you will give it a try, but in exchange you should ask them to repeat: król Karol kupił królowej Karolinie korale koloru koralowego (king Karol has bought a bead necklace of coral colour for queen Karolina). You can rest assured that it’s not going to be an easy task.

Let’s not forget that most Poles have been learning these tongue-twisters all their lives. When they rattle them off without pausing for breath, you can be sure they have done it many times before.

And if you want to pleasantly surprise both the Poles and foreigners speaking Polish, it is enough, while spending time in your cosy domesticity, to memorize one of such tongue-twisters (in case of difficulties just ask your teacher for help), and then to show what you can do. And then, it will turn out that Polish is easy after all (and especially so, when you learn it at Po Polsku)!

wtorek, 13 października 2015

MIGRATING "SIĘ", OR A VERY FLEXIBLE POLISH PHRASE :)

WHERE SHOULD SELF (SIĘ) FIND ITSELF? ;)

A simple question with an equally simple answer it would seem, but then again very often asked during the Polish language courses. Students are quite concerned with the fact that they hear the reflexive pronoun się in different parts of a sentence. Is it possible that the position of this pronoun is … random? Well,… very often… it is. It mainly applies to questions. We can say jak się pani nazywa? and jak pani się nazywa? (literally how do you call yourself, lady/miss?) and still, both questions are correct! There is no difference between: jak się pan czuje? and jak pan się czuje? (literally how do you feel yourself, sir/mister?); gdzie znajduje się centrum? and gdzie się znajduje centrum? (literally where does the centre find itself meaning where is the centre located); dlaczego się jeszcze nie umyłeś? and dlaczego nie umyłeś się jeszcze? (literally why haven’t you washed yourself yet); gdzie się tak przeziębiłeś? and gdzie tak się przeziębiłeś? (literally where have you caught yourself a cold).

POSITION OF SIĘ IN A POLISH SENTENCE. ARE THERE ANY RULES?

Yes, there are rules. In principle, we should use się neither at the beginning of a sentence nor after a preposition. Accordingly, the question z się czego pan śmieje? doesn’t make sense. Instead, it should sound z czego się pan śmieje? or z czego pan się śmieje? (meaning what are you laughing at, sir/mister?). In affirmative sentences it’s best to position się just behind the verb (Obejrzałam się za siebie – I looked behind; Rozgadał się strasznie – He rambled on and on; Nasłuchał się głupot – He heard a lot of nonsense; Umówiła się ze mną na dworcu – She arranged to meet me at the station etc.). The pronoun się can be found at the end of a sentence if this sentence consists of a predicate only, for instance: Napijesz się? (Do you care for a drink?); Rozpadało się (It started to rain); Wypogodziło się (It [the sky] cleared up); Odsuń się (literally Back yourself off); Pogodziliśmy się (We made it up); Pokłóciliśmy się (We had a row).

SIĘ AND COLLOQUIAL POLISH PHRASES

It might happen that you hear się at…the beginning of a sentence. If you want to emphasise that a situation is very complicated and that it’s going to be hard to deal with it, you can say Się porobiło (literally It has done itself); someone’s ridiculous comment we disapprove of we can sum up (with a dose of sarcasm) Się wypowiedział (literally He expressed himself); to vigorously express your engagement and pride in something, we can use a phrase Się pomaga! (literally It helps itself! meaning I’m helping here). However, from point of view of grammar, these phrases are incorrect and they are chiefly used in informal, spoken language. Time will tell if such expressions will be incorporated into the Polish language for good, or if they are just a passing fad.

Test your Polish with us. Check out our FB profile

A simple question with an equally simple answer it would seem, but then again very often asked during the Polish language courses. Students are quite concerned with the fact that they hear the reflexive pronoun się in different parts of a sentence. Is it possible that the position of this pronoun is … random? Well,… very often… it is. It mainly applies to questions. We can say jak się pani nazywa? and jak pani się nazywa? (literally how do you call yourself, lady/miss?) and still, both questions are correct! There is no difference between: jak się pan czuje? and jak pan się czuje? (literally how do you feel yourself, sir/mister?); gdzie znajduje się centrum? and gdzie się znajduje centrum? (literally where does the centre find itself meaning where is the centre located); dlaczego się jeszcze nie umyłeś? and dlaczego nie umyłeś się jeszcze? (literally why haven’t you washed yourself yet); gdzie się tak przeziębiłeś? and gdzie tak się przeziębiłeś? (literally where have you caught yourself a cold).

POSITION OF SIĘ IN A POLISH SENTENCE. ARE THERE ANY RULES?

Yes, there are rules. In principle, we should use się neither at the beginning of a sentence nor after a preposition. Accordingly, the question z się czego pan śmieje? doesn’t make sense. Instead, it should sound z czego się pan śmieje? or z czego pan się śmieje? (meaning what are you laughing at, sir/mister?). In affirmative sentences it’s best to position się just behind the verb (Obejrzałam się za siebie – I looked behind; Rozgadał się strasznie – He rambled on and on; Nasłuchał się głupot – He heard a lot of nonsense; Umówiła się ze mną na dworcu – She arranged to meet me at the station etc.). The pronoun się can be found at the end of a sentence if this sentence consists of a predicate only, for instance: Napijesz się? (Do you care for a drink?); Rozpadało się (It started to rain); Wypogodziło się (It [the sky] cleared up); Odsuń się (literally Back yourself off); Pogodziliśmy się (We made it up); Pokłóciliśmy się (We had a row).

SIĘ AND COLLOQUIAL POLISH PHRASES

It might happen that you hear się at…the beginning of a sentence. If you want to emphasise that a situation is very complicated and that it’s going to be hard to deal with it, you can say Się porobiło (literally It has done itself); someone’s ridiculous comment we disapprove of we can sum up (with a dose of sarcasm) Się wypowiedział (literally He expressed himself); to vigorously express your engagement and pride in something, we can use a phrase Się pomaga! (literally It helps itself! meaning I’m helping here). However, from point of view of grammar, these phrases are incorrect and they are chiefly used in informal, spoken language. Time will tell if such expressions will be incorporated into the Polish language for good, or if they are just a passing fad.

Test your Polish with us. Check out our FB profile

piątek, 2 października 2015

WHAT DOES THE POLISH GOLDEN AUTUMN HAVE TO DO WITH APPLES?

WHAT IS ‘BABIE LATO’ ACTUALLY?

The summer is gone, the hot days have passed. The time of Indian summer or babie lato and Polish golden autumn has come, but still, the sun keeps reminding us of the summer holidays. The days are still warm, the sky is blue and the foliage of the trees is slowly turning golden, red, and brown. This is also the moment when many foreigners decide to attend a course of Polish . Rested after the summer holidays, encouraged by the language progress made during the intensive summer lessons, they enroll on regular courses and over the next few months, regularly, two or three times a week, they are going to explore the secrets of the Polish language (more information on that you can find on our FB profile).

SWEET SECRET

This is also a period when the most popular Polish pie – apple pie or szarlotka - tastes perhaps the best. Why best? Because it is made with apples that are very juicy and sweet at the beginning of autumn, and therefore ideal for making a szarlotka. And you really don’t need to be a master chef to be able to make it. A good recipe will suffice. How many recipes are there? As many as there are cookery books or perhaps even more, since everybody who cooks and bakes from time to time has their own sweet secret.

The most important thing, however, is to use high quality flour, butter, eggs and only a small amount of sugar, and of course, lots and lots of apples (preferably the Polish ones). Often, at this time of year, this popular pie is made with fresh and not roasted apples. The deliciously sweet smell of apples, cut or grated, sprinkled with sugar, vanilla or cinnamon will waft across the house.

Nothing will give you as much energy to learn Polish as a piece of sweet szarlotka :)

POLISH RECIPE FOR HOW TO PRESERVE A PIECE OF SUMMER FOR THE WINTER

Many provident fans of szarlotka prepare the supplies of sweet, roasted apples for the wintertime, so during cold winter evenings, while doing their Polish language homework, they can nibble on their favourite pie and recall the sunny summertime for at least a moment.

Enjoy :)

The summer is gone, the hot days have passed. The time of Indian summer or babie lato and Polish golden autumn has come, but still, the sun keeps reminding us of the summer holidays. The days are still warm, the sky is blue and the foliage of the trees is slowly turning golden, red, and brown. This is also the moment when many foreigners decide to attend a course of Polish . Rested after the summer holidays, encouraged by the language progress made during the intensive summer lessons, they enroll on regular courses and over the next few months, regularly, two or three times a week, they are going to explore the secrets of the Polish language (more information on that you can find on our FB profile).

SWEET SECRET

This is also a period when the most popular Polish pie – apple pie or szarlotka - tastes perhaps the best. Why best? Because it is made with apples that are very juicy and sweet at the beginning of autumn, and therefore ideal for making a szarlotka. And you really don’t need to be a master chef to be able to make it. A good recipe will suffice. How many recipes are there? As many as there are cookery books or perhaps even more, since everybody who cooks and bakes from time to time has their own sweet secret.

The most important thing, however, is to use high quality flour, butter, eggs and only a small amount of sugar, and of course, lots and lots of apples (preferably the Polish ones). Often, at this time of year, this popular pie is made with fresh and not roasted apples. The deliciously sweet smell of apples, cut or grated, sprinkled with sugar, vanilla or cinnamon will waft across the house.

Nothing will give you as much energy to learn Polish as a piece of sweet szarlotka :)

POLISH RECIPE FOR HOW TO PRESERVE A PIECE OF SUMMER FOR THE WINTER

Many provident fans of szarlotka prepare the supplies of sweet, roasted apples for the wintertime, so during cold winter evenings, while doing their Polish language homework, they can nibble on their favourite pie and recall the sunny summertime for at least a moment.

Enjoy :)

piątek, 18 września 2015

CHLEB I BUŁKA (bread and bread roll), OR POLISH IDIOMS AND BAKERY PRODUCTS

SHOPPING IN POLISH CLASSES

Students of Polish very often ask not only how to do the shopping in Polish (check here for more on that), but also what to call some basic foodstuffs. One of the nouns that are taught at the very beginning within this vocabulary range is chleb (bread). Later, during the course you will find out in what idioms this noun is used. Let’s take a closer look at some of them.

LEARNING POLISH. CIĘŻKI KAWAŁEK CHLEBA?!

When we’re talking about people who go abroad to look for better job opportunities, we say that they wyjeżdżają za chlebem (that is to improve the standard and conditions of their lives). Living far from home and friends, in new environment, must be ciężki kawałek chleba (literally: a tough piece of bread; a hard way to make a living). This idiom may refer not only to the issue of labour migration, but any activity or task that is difficult for you or involves mental or physical effort. One of the advantages of such travel is the possibility to get to know new cultures and customs, and after some time the traveller can say that he or she z niejednego pieca chleb jadł (literally: has eaten bread from more than one oven; he/she has seen quite a few things), i.e. they have a lot of life experience.

Just as the expression ciężki kawałek chleba this idiom does not only refer to travel experience. Anyone who has a wealth of experience in any area of life may say z niejednego pieca chleb jadłam/jadłem. And gaining new experience is chleb powszedni for people like that (i.e. nothing unusual, something common, natural).

We can encounter obstacles in every part of our lives (our relationship, work, hobby, project), and then we can comment, discouraged: z tej mąki chleba nie będzie (literally: one can’t make bread with this flour), i.e. it’s a fruitless effort, with no chance of success.

more vocabulary on our FB profile

POLISH COURSE. BUŁKA Z MASŁEM?

When we are not frightened by the obstacles and believe that we’ll overcome them easily, we say it’s bułka z masłem (literally: a roll with butter; a piece of cake), which means it’s easy, not too complicated. Reading a crime story in Polish may turn out to be bułka z masłem. If the crime story is popular we can imagine it rozszedł się jak świeże bułeczki (sold like hot cakes), i.e. it sold very well. And if the author of the book complains about the loss of privacy as a result of their success, we can state that they chciał(a)by on/ona zjeść ciasto i mieć ciastko (would like to have their cake and eat it, too), which means they want things that can’t possibly go together, they exlude each other.

As you can see, we use the names of foodstuffs to say something more than just describe what we had for breakfast.

Students of Polish very often ask not only how to do the shopping in Polish (check here for more on that), but also what to call some basic foodstuffs. One of the nouns that are taught at the very beginning within this vocabulary range is chleb (bread). Later, during the course you will find out in what idioms this noun is used. Let’s take a closer look at some of them.

LEARNING POLISH. CIĘŻKI KAWAŁEK CHLEBA?!

When we’re talking about people who go abroad to look for better job opportunities, we say that they wyjeżdżają za chlebem (that is to improve the standard and conditions of their lives). Living far from home and friends, in new environment, must be ciężki kawałek chleba (literally: a tough piece of bread; a hard way to make a living). This idiom may refer not only to the issue of labour migration, but any activity or task that is difficult for you or involves mental or physical effort. One of the advantages of such travel is the possibility to get to know new cultures and customs, and after some time the traveller can say that he or she z niejednego pieca chleb jadł (literally: has eaten bread from more than one oven; he/she has seen quite a few things), i.e. they have a lot of life experience.

Just as the expression ciężki kawałek chleba this idiom does not only refer to travel experience. Anyone who has a wealth of experience in any area of life may say z niejednego pieca chleb jadłam/jadłem. And gaining new experience is chleb powszedni for people like that (i.e. nothing unusual, something common, natural).

We can encounter obstacles in every part of our lives (our relationship, work, hobby, project), and then we can comment, discouraged: z tej mąki chleba nie będzie (literally: one can’t make bread with this flour), i.e. it’s a fruitless effort, with no chance of success.

more vocabulary on our FB profile

POLISH COURSE. BUŁKA Z MASŁEM?

When we are not frightened by the obstacles and believe that we’ll overcome them easily, we say it’s bułka z masłem (literally: a roll with butter; a piece of cake), which means it’s easy, not too complicated. Reading a crime story in Polish may turn out to be bułka z masłem. If the crime story is popular we can imagine it rozszedł się jak świeże bułeczki (sold like hot cakes), i.e. it sold very well. And if the author of the book complains about the loss of privacy as a result of their success, we can state that they chciał(a)by on/ona zjeść ciasto i mieć ciastko (would like to have their cake and eat it, too), which means they want things that can’t possibly go together, they exlude each other.

As you can see, we use the names of foodstuffs to say something more than just describe what we had for breakfast.

piątek, 4 września 2015

POLISH ACCENT AT THE END OF THE WORLD

SCHOOLS ABROAD NAMED AFTER POLISH PEOPLE

More and more frequently we choose to spend our holiday at distant destinations. We are not only driven by the fashion for trips to exotic, isolated islands or unexplored lands, but also by the desire to get to know other cultures, languages and people. As the Polish saying goes podróże kształcą, i.e. travel broadens the mind (and you can enrol on a course of Polish during the holiday )

Distant, unknown countries may surprise us in many ways. It might turn out that while being a few thousand kilometres away we will come across some streets named after Polish people, or monuments erected to commemorate them by the inhabitans of those distant countries, or even species of animals and plants having the names of the Poles who discovered them.

POLISH BOTANIST IN THE CAUCASUS

If you go to Georgia and visit Lagodekhi National Park, right at the entrance you’ll see a plaque commemorating Ludwik Młokosiewicz. He was a Polish botanist known for exploring the fauna and flora of the Caucasus, who found himself in the region of today’s Kakheti. He was the first one to notice that many species inhabiting the area were unique, indigentous to that particular region. He spared no effort and as a result it was decided that those species would be protected and a national park was created. If you tell the museum employees that you come from Poland, they will definitely treat you with great respect and encourage you to visit the local Polish community. While there you should also try to spot the Caucasian grouse (Tetrao mlokosiewiczi) and Caucasian peony (Paeonia mlokosewitschii).

In Lagodekhi National Park there is also a stone commemorating Ludwik Młokosiewicz (check out FB profile for more interesting facts about well-known Polish people)

A CHILEAN CITIZEN SPEAKING POLISH

If one day you are in the streets of a Chilean city, walking and speaking Polish, don’t be surprised when smiling Chileans approach to speak to you. Why? We owe it to Ignacy Domeyko. In almost every city you can find a street, square or school named after him. He was a Polish engineer and geologist, born in the early 19th century. Not only did he discover rich deposits of copper in Chile and teach the people of Chile how to benefit from that, but also reformed the local education system. Moreover, Domeyko started the struggle against illiteracy and thanks to him the University of Santiago became one of the leading universities in the country. Ignacy was granted Chilean citizenship for his contribution. He lived there until he died, but he never forgot his mother tongue.

HEADING FOR THE MOUNTAINS

While staying in Peru you’ll find out that a Pole, Enrest Malinowski, is one of their national heroes. He was the one who brought sailors…to work in the mountains. Sounds ridiculous? Only at first. He was an engineer who designed Ferrocarril Central del Perú (one of the Trans-Andean Railways) and oversaw the construction process. The railway linked the two parts of Peru that had been separated before. The sailors could climb ropes easily, which was an invaluable skill under the circumstances, since the tracks were put high in the mountains. Malinowski personally helped the workmen, he worked with them all the time and endured the same hardships as they did, despite the fact that he had a fancy apartment in the capital city and could have stayed there.

Thanks to him, the highest railway in the world was built (the highest bridge is as high as 80m!), and it’s used to transport goods and raw materials.

As you can see, even very far from Poland, a Pole does not necessarily need to feel like a foreigner at all:)

More and more frequently we choose to spend our holiday at distant destinations. We are not only driven by the fashion for trips to exotic, isolated islands or unexplored lands, but also by the desire to get to know other cultures, languages and people. As the Polish saying goes podróże kształcą, i.e. travel broadens the mind (and you can enrol on a course of Polish during the holiday )

Distant, unknown countries may surprise us in many ways. It might turn out that while being a few thousand kilometres away we will come across some streets named after Polish people, or monuments erected to commemorate them by the inhabitans of those distant countries, or even species of animals and plants having the names of the Poles who discovered them.

POLISH BOTANIST IN THE CAUCASUS

If you go to Georgia and visit Lagodekhi National Park, right at the entrance you’ll see a plaque commemorating Ludwik Młokosiewicz. He was a Polish botanist known for exploring the fauna and flora of the Caucasus, who found himself in the region of today’s Kakheti. He was the first one to notice that many species inhabiting the area were unique, indigentous to that particular region. He spared no effort and as a result it was decided that those species would be protected and a national park was created. If you tell the museum employees that you come from Poland, they will definitely treat you with great respect and encourage you to visit the local Polish community. While there you should also try to spot the Caucasian grouse (Tetrao mlokosiewiczi) and Caucasian peony (Paeonia mlokosewitschii).

In Lagodekhi National Park there is also a stone commemorating Ludwik Młokosiewicz (check out FB profile for more interesting facts about well-known Polish people)

A CHILEAN CITIZEN SPEAKING POLISH

If one day you are in the streets of a Chilean city, walking and speaking Polish, don’t be surprised when smiling Chileans approach to speak to you. Why? We owe it to Ignacy Domeyko. In almost every city you can find a street, square or school named after him. He was a Polish engineer and geologist, born in the early 19th century. Not only did he discover rich deposits of copper in Chile and teach the people of Chile how to benefit from that, but also reformed the local education system. Moreover, Domeyko started the struggle against illiteracy and thanks to him the University of Santiago became one of the leading universities in the country. Ignacy was granted Chilean citizenship for his contribution. He lived there until he died, but he never forgot his mother tongue.

HEADING FOR THE MOUNTAINS

While staying in Peru you’ll find out that a Pole, Enrest Malinowski, is one of their national heroes. He was the one who brought sailors…to work in the mountains. Sounds ridiculous? Only at first. He was an engineer who designed Ferrocarril Central del Perú (one of the Trans-Andean Railways) and oversaw the construction process. The railway linked the two parts of Peru that had been separated before. The sailors could climb ropes easily, which was an invaluable skill under the circumstances, since the tracks were put high in the mountains. Malinowski personally helped the workmen, he worked with them all the time and endured the same hardships as they did, despite the fact that he had a fancy apartment in the capital city and could have stayed there.

Thanks to him, the highest railway in the world was built (the highest bridge is as high as 80m!), and it’s used to transport goods and raw materials.

As you can see, even very far from Poland, a Pole does not necessarily need to feel like a foreigner at all:)

Subskrybuj:

Posty (Atom)